4 Investigates: Teens and violent crime in the metro

“It’s very easy to get your hands on a gun,” said Dennica Torres, district defender for the Law Offices of the Public Defender in the Second Judicial District. “They literally just have to go on social media.”

It’s one answer to a question we’ve all been asking. What’s behind a growing trend of children using guns to commit violent crimes?

“There’s probably never been more access to guns in our history,” said Albino Garcia, founder of La Plazita Institute.

We’ve seen carjackings, armed robberies, and murders just this year alone. Horrific crimes are being committed by children.

“Just a couple of months into me having this job we recognized that fact that juvenile crime and juveniles with guns is a real problem in our community,” said Bernalillo County District Attorney Sam Bregman.

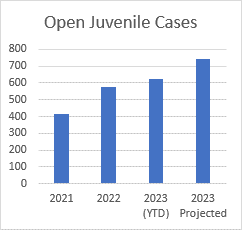

Bregman said his office is on pace to open nearly 800 juvenile criminal cases this year, up 30% from last year.

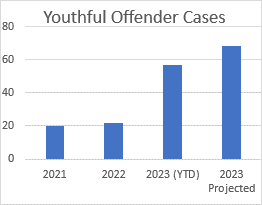

Violent felonies like robbery or second-degree murder, what the court calls Youthful Offender cases, have nearly tripled.

Dennica Torres is with the Law Offices of the Public Defender, which often represents kids accused of serious crimes. These days, she said, many of them don’t have a record.

“Most of the kids getting in trouble for gun violence, it’s their first referral, it’s the first time they’ve had an experience with the juvenile justice system and a lot of that comes from peer pressure,” Torres said.

No one knows that problem quite like La Plazita Institute, a South Valley organization that works with system-impacted youth.

“When I ask kids why they carry guns and they say out of protection and fear,” said Albino Garcia.

Many employees there are mentors, people with lived experience, like Siddiq Silguero, who is very much a work in progress.

“I know what it’s like to have a gun, to be riding around with your homies and wanting to shoot things up and for no reason just to know what it feels like,” said Silguero. “That sounds sick that sounds twisted, but our youth are going through that.”

Now an adult on federal probation, he’s a non-active gang member and recovering heroin addict. He said he grew up in a single-family household, where he learned about being a man from what he saw on the streets.

“About 15 years old is when I started selling drugs, I first got my first little gun,” he said. “16,17 is when I started getting my hands on a lot more drugs. And then 18, 19 is when I started robbing people and started using that gun for a whole bunch of other stuff.”

Youthful Offender: A delinquent child who is 14 to 18 years of age and is adjudicated for at least one of the following: Second degree murder, Assault with intent to commit a violent felony, kidnapping, aggravated battery, shooting at a dwelling, dangerous use of explosives, criminal sexual penetration, robbery, aggravated burglary, aggravated arson, abuse of child resulting in great bodily harm.

It’s a story that seems to be playing out for younger and younger New Mexicans. Garcia blames it on the complete lack of resources for education and prevention.

“In order to impact and reduce the violence, it isn’t more cops. Give us the money. Give us the money,” Garcia said. “We will put people in the schools. They will break down the tensions and the conflicts and kids will shoot each other less. I am positive of that.”

Right now, the biggest tool isn’t prevention at all. It’s intervention.

“Young people are hungry for services or guidance,” said Tanya Tijerina, clinical operations manager for Second Judicial District Court. “They may not know that. But the truth is the want and the need is there.”

Tijerina helped create the Community Gun Violence Intervention program under Bernalillo County District Court three years ago.

It’s a 16-week diversion for children who have current gun charges. The program is so impactful, out of a hundred kids who’ve gone through it, so far only one, who completed the course, went on to pick up another violent felony.

But the demand is exceeding capacity. The waitlist is getting longer.

“Young people are experiencing trauma. It’s hard right now. It’s hard to grow up without parents or grow up without your basic needs met. It’s hard to grow up without opportunity,” said Tijerina.

There’s more pressure than ever to get crime under control.

“When someone is 13, 14, 15 years old, if we don’t do what’s right for them, if we don’t hold them accountable in some way and they don’t learn anything from it, my fear is that they never leave the criminal justice system, that they keep going back to it,” said DA Bregman.

But advocates worry about a knee-jerk response, pointing to the state’s most recent public health order that aims to lock up more juvenile offenders.

“Incarcerating them doesn’t do anything but help create career criminals,” said Torres.

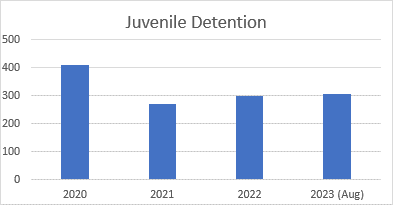

Juvenile booking into the Bernalillo County Juvenile Detention Center has decreased since 2020.

Ahead of the 2024 legislative session, Torres wants solutions that are proven to work – a direction perhaps best taken by someone who’s been there.

“If we give them a space, a safe place to give them that attention, to get one-on-ones, get groups going on and give them activities, things to do,” said Silguero.

An option he didn’t have. He thought back to when he was growing up without a role model and a mentor to guide him. Something he said robbed him of a brighter future.

“Because I didn’t tell on somebody, because I went to prison. Because I kept it solid, I didn’t get a better credit score,” said Silguero. “I can’t get certain jobs because of that. I can’t get certain apartments because of that because of my felony record. I can’t own a gun. I can’t do a number of things because of what I was so eager to throw my life away for. At 34, it means absolutely nothing.”