4 Investigates: New Mexico’s CARA Program

ALBUQUERQUE, N.M. — Seeking better lives for newborn babies and addicted parents, New Mexico has a plan to keep families together and get them the services they need. But the state is missing key data points to tell if the plans are leading to better outcomes.

Substance abuse can have heartbreaking consequences, not just for those fighting addiction.

New Mexicans learned firsthand, in June 2022 when a Socorro baby, Ricky Renova, died after ingesting Fentanyl. His mother, Elisa Renova, admitted to using the drug earlier that morning. According to lapel video of the incident, Ricky was almost two years old.

To address situations like that one, in 2019 the legislature created a New Mexico CARA program, using the federal Comprehensive Addiction Recovery Act, which aims to keep mom and baby together with supportive services.

HB 230 brought New Mexico into compliance with federal Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act requirements.

“It really pushed state child welfare agencies to develop these plans of care to start working with substance-using parents and substance-exposed newborns early on instead of waiting for an abuse and neglect call or intervention,” said Milissa Soto, federal reporting bureau chief for CYFD Protective Services.

It also eliminates the abuse-reporting requirements to CYFD. While hospital workers are still mandated reporters, and can still report suspected abuse to CYFD, substance use alone would no longer require a report of abuse.

In doing that, the hope was that more women would be unafraid to get help.

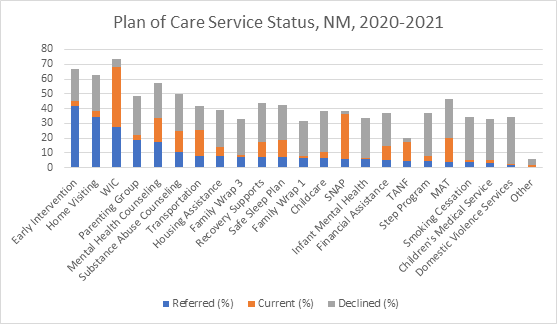

“It’s not just mental health of substance abuse services, although that’s key, it’s also providing access to things like WIC, TANF, or childcare, or snap or even transportation,” said Soto.

Dr. Andrew Hsi had a hand in the bill using his decades of experience working with women using during pregnancy.

“So our plan in New Mexico recognized that babies do well when they’re with their mothers, when their mothers are doing well,” said Dr. Hsi, a retired professor at the UNM Health Sciences Center, and chair of the J. Paul Taylor Task Force.

After a hospital identifies a substance-exposed newborn, they fill out a Plan of Care. They work with the mother, to see if she wants services, and what kind – anything from home visiting, financial assistance, to counseling. Then they indicate if the mother agrees to the plan.

From there, the wheels start spinning, shooting information to state agencies like CYFD and the New Mexico Department of Health. Insurance care coordinators are supposed to get those moms connected to services and serve as the in-between.

Since the program started in 2020 almost 3,000 confidential plans have been created.

But what happens next is fuzzy. NMDOH data tracks what mothers initially say to participate but not the number of women who end up accessing those services and for how long.

“Referred, current and declined” correlate to the bubbles selected when completing the plan of care.

Plan of Care documents are confidential. But we do know babies are still dying. KOB 4 pulled autopsies for children under two this year. There were 19 reports. Nine of those mentioned drugs either ingested by the baby, in utero exposure or suspected use from parents.

Two reports specifically name fentanyl as the cause of death. That does not include Ricky’s case.

“Me myself, you send me home with this packet, and I’m probably not going to read it, honestly,” said Stacy Burleson. Burleson runs a group, called Women in Leadership, which supports women impacted by the criminal justice system.

“What is support? What does support look like for someone struggling with substance use? A woman struggling with substance use, you pretty much have to show them everything you have to take them hand in hand and guide them,” said Burleson.

Those concerns were brought up at the Roundhouse in 2019.

“This plan that you developed doesn’t really have any oversight,” said State Rep. Kelly Fajardo. “It doesn’t have any follow through to me, there’s no accountability.”

According to CYFD, from 2020 to 2021, nine infants, with a plan of care or notification, died within their first year, and many of those were also reported for child abuse.

“Seven out of the 9 cases were reported to SCI at the time of birth. One had current CYFD involvement at the time of baby’s birth, and 1 of 9 was not reported to SCI.”

CYFD went into further detail on those cases:

“The CARA team has done internal reviews of these cases and have found themes that may have contributed to heightened risk for CARA newborns/infants. Due to the pandemic, prenatal healthcare was difficult to access and impacted the quality of care that women received. This is in addition to national data that shows women with substance use do not access prenatal care regularly or at all. Newborns with substance exposure can have medical conditions such as prematurity, low birth weight and other conditions that make them more vulnerable to complications. Finally, parent implementation of safe sleep practices and access to resources such as cribs and other safe sleep environments was a reoccurring theme in all 9 cases.”

The legislation does say CYFD should be notified if families fail to follow the plan but that, too, is not being done or tracked.

“I know it’s in the statute, non-compliance, but I don’t like that word because this is a voluntary program. We are doing follow up,” said Soto.

CYFD said CARA navigators are successfully following up with families who decline services. But once more, the state agency does not have data that measures that success.

There is a comprehensive evaluation report put together by the Department of Health for fall 2021. The 2022 report is still in the works.

“The report, that would include 2021 data, isn’t complete yet because we’ve been working on some other analysis,” said Nick Sharp, epidemiologist and evaluator with the Department of Health in the Maternal Childhood Health Epidemiology Program.

Officials with CYFD and DOH said the program needs more funding and resources to reach its full potential, with the goal of expanding to prenatal plans of care.

“I think the next steps are one, making sure the behavioral health systems and treatment systems become robust enough to offer care to every mother and family member that have a substance use disorder they want to seek treatment for, secondly, to create an integrated database system that protects people’s privacy but that allows long-term follow up,” said Dr. Hsi.

Because participation is confidential we don’t know if Elisa Renova ever agreed to this type of plan. She is now charged with the death of her baby boy – an example of how difficult it can be to succeed.