4 Investigates: CYFD office stays

Our child welfare system is in a state of crisis, but just how bad it’s become is hard to know.

KOB 4 has waited for months to see records of police calls to an Albuquerque office where kids removed from unsafe homes are sleeping, waiting for a real home and a real bed.

What she uncovered shows how dangerous it can be for kids when the state Department of Children Youth and Families says it’s there to help them.

The Albuquerque CYFD building on Indian School may not look like much, but it’s home, sort of.

“It smells horrible. There’s trash. There’s stuff spilt everywhere. They’re smoking fentanyl in there,” said Evan Sena, a former CYFD Permanency Planning Caseworker.

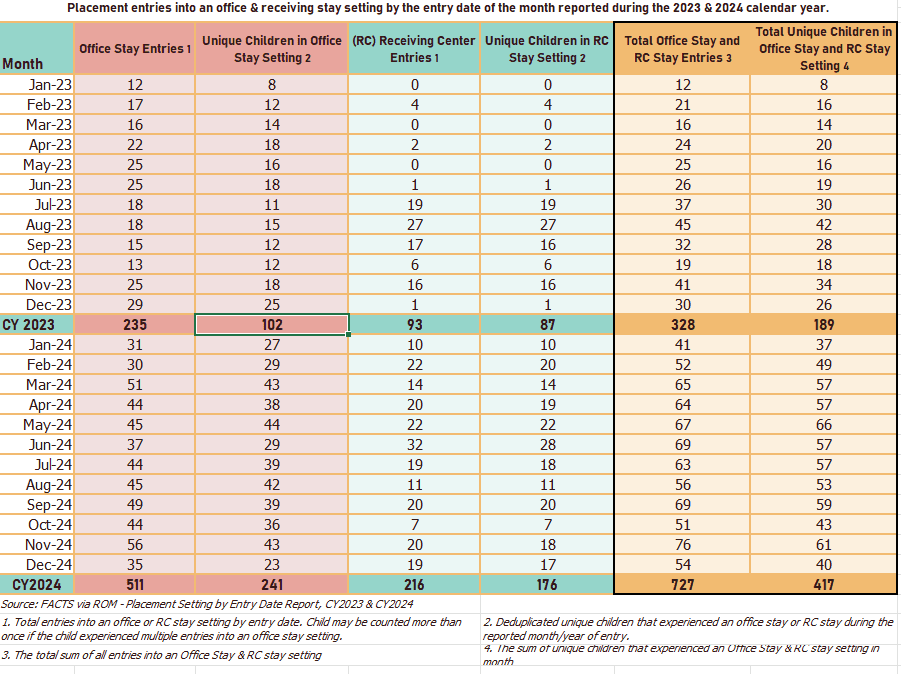

Our Children Youth and Families Department has turned offices around the state into a place to stay for more than 400 kids in 2024.

“It’s a recipe for injury, assault,” said Attorney Sara Crecca. “Beyond basic needs not being met, it’s a dangerous scenario.”

At times, it seems like uncontrollable chaos.

Sena said he’s seen “fights, security guards slamming kids into the wall.”

Our records show CYFD staffers like Evan Sena called police here more than 400 times in a year.

“Everyone has said it has never been so bad,” said Sena.

Alyssa, a child who spent more than a decade is CYFD custody, told us sleeping in the office isn’t much better than an abusive home.

“I just kind of ran away from CYFD. I couldn’t handle sleeping in an office anymore. I was getting so depressed. It was hurtful to go through it,” said Alyssa.

Alyssa was removed from her home at age 7. Then she bounced from foster home to foster home.

“It kind of just felt like there was no one who really wanted me,” she said.

At 16, she ended up at the CYFD office.

Alyssa said the department “had us sleeping on like floors, and they would give us prison food.”

Literally. She said a frozen, reheated pizza from the Juvenile Detention Center was dinner.

“They’re living in a room like this. Half the size of this. They are constantly being monitored. Constantly being watched,” said Sena.

Sena said he burned out, then was forced out.

“I enjoy the work, I just wish we had help,” said Sena. “I don’t think people realize what’s going on and that agency is just going to collapse.”

The director of protective services told employees in February, CYFD will punish those who refuse mandatory overtime for office stays.

“You’re putting youth who need to have their needs met by a parent, and they are put in a home with kids who desperately need a parent, the attention of a loving adult, and they have staff many of whom don’t really want to be there,” said Sara Crecca.

Sara Crecca is Alyssa’s attorney. She’s also part of a team that settled a lawsuit against the department in 2020.

An arbitrator recently said the state is not keeping its promises for system-wide reform. In fact, Crecca says it’s worse.

“The number of children in the office both in Bernalillo County and statewide has exploded,” said Crecca.

It’s doubled in the last year. Often, children sleeping in offices creates more problems for staff. We found calls alleging drug use, police threats to take troubled kids to the detention center and kids running away.

“You’re almost happy when they go, you’re like ‘oh, good, they’re gone,’” said Sena. “Sad to say that, but it’s because we have no help.”

CYFD Secretary Teresa Casados recently told lawmakers, “I want to make it clear that it’s not because we don’t have beds available. We still have beds available for kids that come into care. We don’t have the appropriate type of placement for some of these individuals who might have different trauma, higher needs.”

Secretary Casados wants more money for multiservice group homes. A temporary solution for office stays.

“How do you say what’s better between two evils. The lesser of two evils. Congregate care is not the answer,” said Crecca.

The crisis is so bad, 41 kids in CYFD care are runaways, missing. This month, two teen girls ran off from their group home, Hope House.

Officers said those girls were walking the streets when a man pulled up to them and offered to get them a room for the night. Then, he sexually assaulted them.

“It, to me, is a public health emergency. The fact it hasn’t been treated that way is outrageous,” said Crecca.

“It’s sad that I had to find my forever home by myself,” said Alyssa.

She’s 18 and not sure what’s next. She never finished ninth grade. Now, she wonders what would have been if was never removed by CYFD in the first place.

“I would have rather stayed with my family. Completely a 100% yes,” said Alyssa. “I didn’t ask to be born. So, it sucks not having the support of my family. As much as I want it, there’s nothing I can do about it. It’s realizing if they don’t want to be out, they are missing out on a good, kind-hearted person.”

CYFD told KOB Secretary Casados was unavailable to sit down with us for this story. A spokesperson sent this statement:

“We remain transparent and honest with the legislature about the systemic issues we are addressing, and our budget hearing provided an opportunity to outline the agency’s needs in relation to the Kevin S. settlement and the change we’re creating throughout the state. CYFD must be adequately funded to both address the shortfalls and double down on the positive results we are seeing.

Our commitment to early intervention and prevention is gaining momentum. CYFD’s Family Outreach program has more than doubled its engagement rate in the past year, from 19% to 41% in referrals from providers, protective services, and the families themselves. The program connects these families in need to essential community resources, including nutrition assistance, transportation, education, parenting classes, and medical support.

There is still work to be done, and we are hopeful that the legislature will support the department’s efforts in reducing office stays, fully staffing the agency, and serving New Mexico’s most vulnerable children and youth.”